Static Site Generators

Introduction

To date in this course, you’ve been building web content using HTML. While all markup ends up as HTML in order to be understood by the web browser, writing straight HTML isn’t the only way to create web pages and definitely has some limitations.

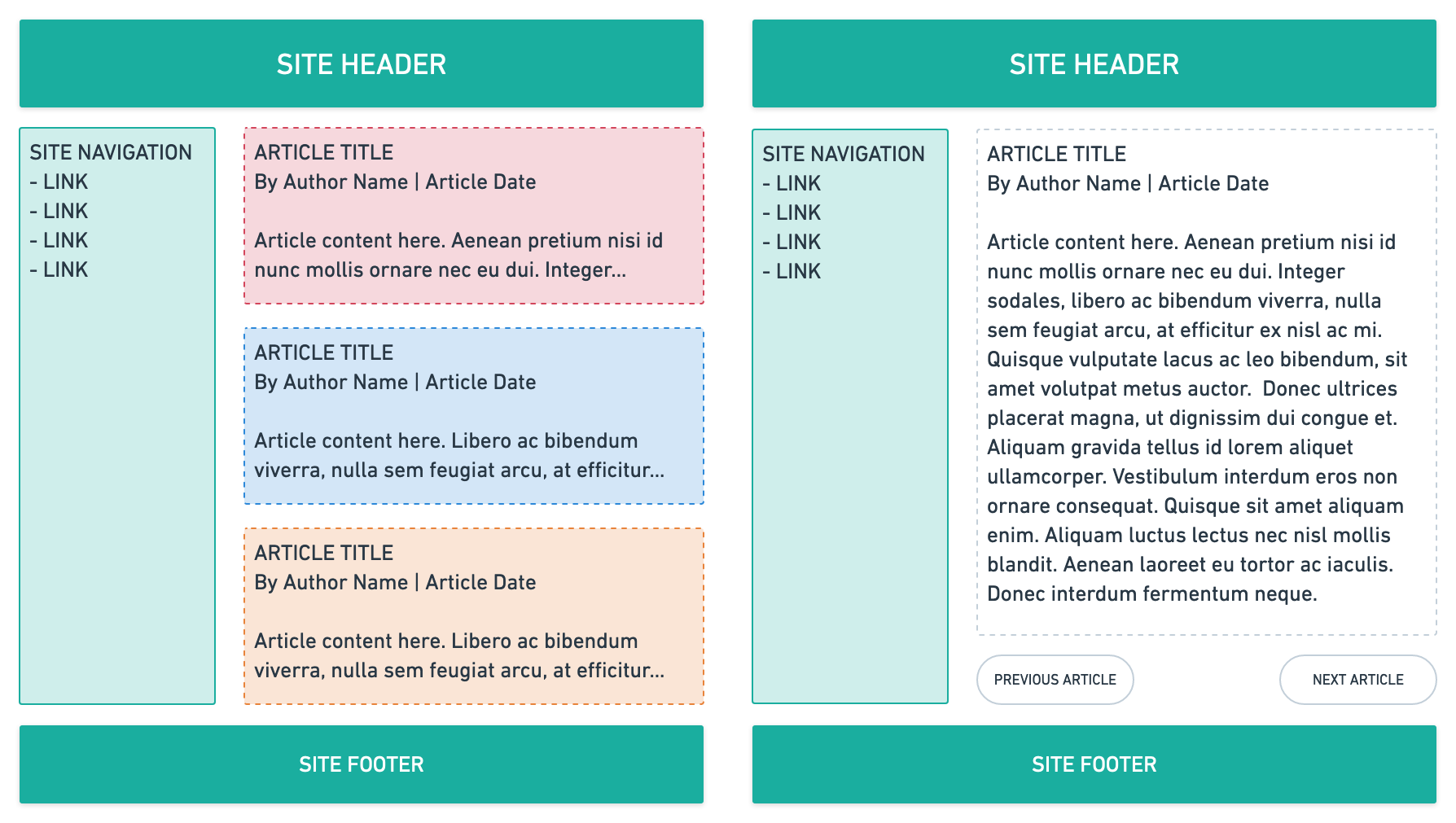

If you consider the following example of a web site layout with the homepage on the left and an individual article layout on the right, you’ll notice that many elements in the site design are repeated or shared between the two pages:

Two layout wireframes are displayed side by side: The layout on the left shows a site header and footer at the top and bottom and, in between, a list of site navigation links and a second list of generic articles. On the right, the layout uses the same header, nav and footer, but a single article replaces the article list.

If you were to recreate these designs in standard HTML, you would be required to repeat all the markup for the site header, navigation and footer on each page, even though there may be no actual changes to that content. Over a site of many pages, that duplication would not only grow tiresome, but updating it – say, if you add a fifth link to the site navigation or add a new social media icon to the site footer – would also be a substantial effort.

Luckily, there’s a different and better way to handle this. 🍀 Using a static site generator, you can create a single HTML file for your site header and use it over and over on as many pages as you create. And that’s only the beginning.

SSG is the acronym for static site generators and will be used from here on out.

Alternatives to SSGs

When creating web sites, your only options are not straight HTML or SSGs. Using programming languages like Ruby, PHP or JavaScript, you can create web sites that are simple or staggeringly complex.

While those languages are outside of the scope of this course, some of the concepts you learn as part of using a SSG will carry over to those languages. For instance, the example I used above of creating a single HTML file for your site header and reusing it across many pages – that file may be called an include, a partial or a component depending on what type of code you’re using to build your site, but the core concept remains the same.

Other alternatives may also use databases to power their web sites. Amazon, for example, uses databases to store a wide variety of information:

- product details, like product names and prices

- user information, like your user name and shipping address

- product reviews, including ratings and user photos

Database-powered web sites are dynamic – that is, the content may not be the same for every user. If I go to the Amazon homepage, the content will change regularly depending on what they are promoting and as sales start and end; if I log in, things will be even further customized based on my past searches and purchases.

Some databases power content management systems (CMSes), which provide GUIs so that users can create and share content online without ever touching code. Sites like WordPress.com, Tumblr and Twitter work this way – while a whole host of code powers these sites, most end users don’t ever see or touch code.

Why use a SSG

While SSGs are more complex than standard HTML, they are significantly less complex than either coding a site using a programming language or maintaining a CMS. They are a great way to explore some programming concepts without having to code everything from scratch. Just like with Sass, where you could continue to write the CSS you already know and sprinkle in Sass goodness as you found helpful – you can write standard HTML for the most part and only introduce the SSG functionality as it’s needed. Compared to web sites backed with a database, sites created with SSGs are usually faster and also more secure (less susceptible to hacking).

Specific SSGs

There are many, many, many SSGs available; this web siteFollowing and reading this link is optional.✳️ lists over 400. 🙀

For example, this web site – your course web site – is built using an open-source SSG written in Ruby called JekyllFollowing and reading this link is optional.✳️ .

You’ll be learning how to use a SSG named Eleventy.Following and reading this link is optional.✳️ It is an open-source project (you can view its code on GitHubFollowing and reading this link is optional.✳️ ) and is built using JavaScript.